Traversing New Terrain: Registering Boston’s Women Voters in 1920

What exactly did these endeavoring women have to bring with them to successfully register as a voter?

Transcribing Boston’s women voter registers for the Mary Eliza Project has revealed countless new avenues through which history can be better understood. From highlighting unsung heroes, underrepresented populations, and remarkable professions of 1920s Boston, these texts demonstrate the impact that the ratification of the 19th Amendment had. With this in mind, it’s vital to consider the steps involved within the registration process itself and what was expected of the women documented in these books.

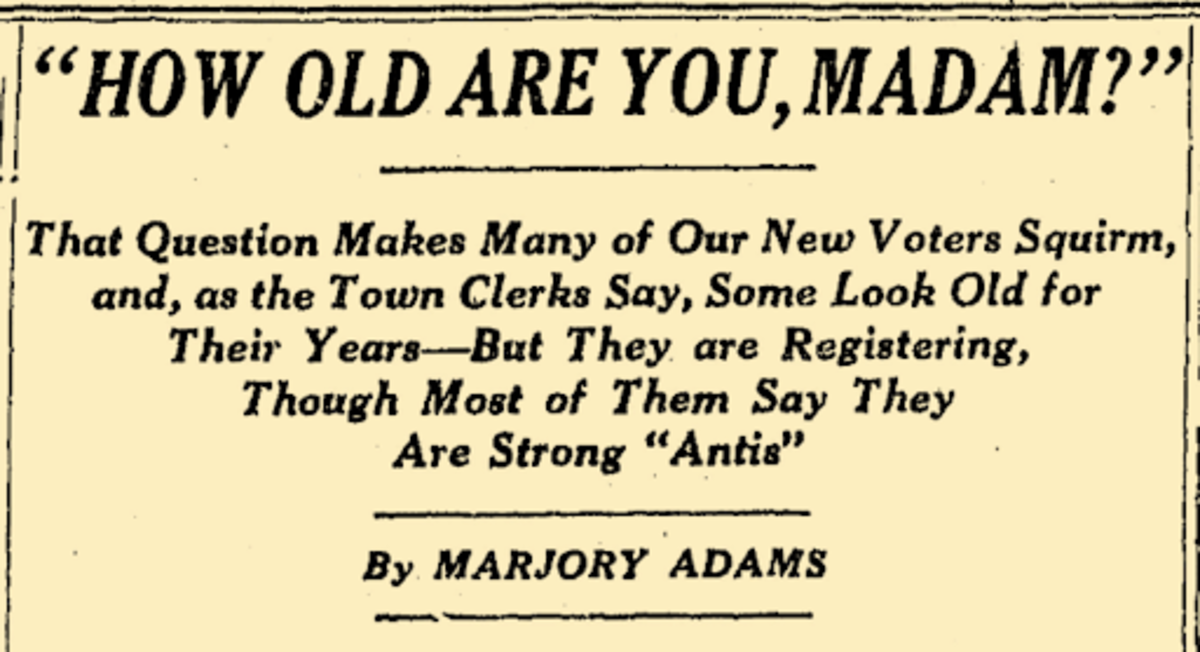

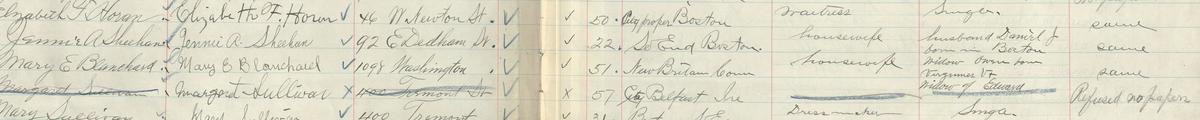

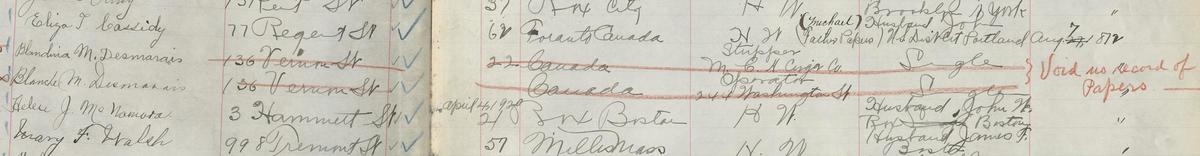

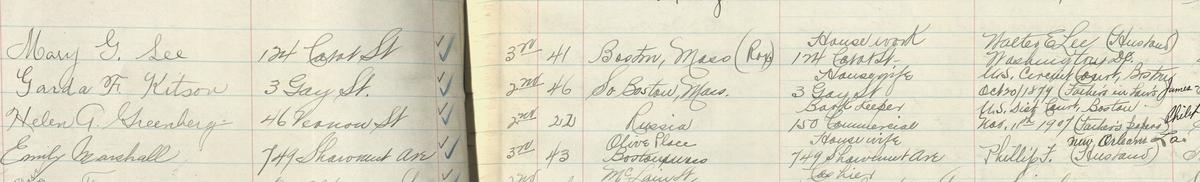

An article published in the Boston Globe on August 29, 1920—entitled “How Old Are You, Madam?”—poked fun at the ensuing chaos at various registration sites, as the city’s women embraced their newly-granted right to vote to varying degrees of success. It noted that registrants are asked to provide their name, address, birthplace, occupation, and age under oath; show proof of American citizenship as needed; and demonstrate their literacy skills by reading lines from the State Constitution. Although the article invited readers to find humor within the scenes of women mistating their ages, misunderstanding the laws around naturalization, and generally grappling with the weight of their civic responsibility, it hides some of the tensions that were part of the experience as well.

Also captured within the registers are snapshots of women who were turned away, whose registration entries were denied or later rendered invalid as their information couldn’t be verified. While some of these women reappear later on attempting to register again, we shouldn’t assume that this was commonplace or that their success was guaranteed. In this sense, there are many partial narratives contained within these books, ones that highlight the women who tried but couldn’t succeed. So, what can we learn from their incomplete stories?

Thinking specifically about naturalization during this time, it’s worth remembering that most foreign-born women couldn’t apply to become American citizens by themselves. For the vast majority, they received their citizenship status through marriage. What the registers reveal, however, goes one step further: If a woman couldn’t provide her own or her husband’s naturalization papers, she could bring in her father’s or father-in-law’s papers instead. In other words, the ability for many women to exercise their voting powers depended largely on their relationships with men. If they couldn’t show proof of a male citizen within their family, their entries would be denied.

There’s no doubt that the fight for suffrage ushered in a new era for women to participate within this country’s democratic processes. But, it also led to the creation of many barriers—poll taxes, literacy tests, citizenship requirements, etc.—that deeply affected the lives of Black, Indigenous, and immigrant women, as well as women with disabilities and limited income. Such a truth can’t be erased or pushed aside, and the Mary Eliza Project was created in hopes of restoring the voices of these women to Boston’s historical narrative. If this interests you, please consider joining us as our dataset continues to grow!

Further Reading:

- What the First Women Voters Experienced When Registering for the 1920 Election, Smithsonian Magazine

- Boston Women Register to Vote, National Park Service

- “Women Take the Ballot Seriously”: Boston Women in the 1920 Election, National Park Service

This blog post was written by Coco Lam. Lam is a dual degree graduate student in History and Archives Management at Simmons University.